“Someday we will build up a world telephone system, making necessary to all peoples the use of a common language or common understanding of languages, which will join all the people of the earth into one brotherhood. There will be heard throughout the earth a great voice coming out of the ether which will proclaim, ‘Peace on earth, good will towards men.'” – John J. Carty (Chief Engineer at AT&T, 1891) (Credit)

“He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee.” – Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

The Internet has brought seemingly limitless information and media, literally, to our fingertips. I have watched my mother reconnect with grammar school friends on a social media site, even though that time was decades past and half a world away. The Internet, like the Post, Telegraph, Radio, Telephone, and Television, have also served to speed information between people at distances far greater than human perception would typically allow. But, there are a few key differences. First is the ubiquity of the Internet. It can be accessed from your phone, your computer, your tablet, from a coffee shop down the street, your 5th floor apartment, your workplace, mid-air, the middle of the ocean, and extra-terrestrially (Twitter). Another difference is the sheer volume of people able to access the information – the International Telecommunication Union estimates that in 2015 3.1 billion (or half the planet’s population) was using the Internet. Virtually everyone has a cell phone (seriously the statistic is 7,085,000,000; the 2015 estimated population for the planet is 7,200,000,000). And of course, programming within the Internet has made information accessible to even more users through automated translation. There is also the depth of interaction, were bandwidth to allow it, all 7 billion users could conceivably be in the same chat room at the same time, passing information back and forth. So why hasn’t Carty’s prediction come true?

Well, Z isn’t going to sort out this thornier philosophical issue for you (an excellent place to get started, however, is Ted Robert Gurr’s Why Men Rebel,1970). Spoiler alert: academia still hasn’t come to an agreement (Z suspects the answer is both – nurture and nature, based on his observations).

The last 12-months has thrown into stark relief the impact that anti-social media (meant in its correct sense: unwilling or unable to associate in a normal or friendly way with other people) has on engendering a distinctive anti-social environment.

To put it plainly, the Internet empowers demagogues and provides a platform where one can find supportive listeners, watchers, activists, and foot soldiers anywhere in the world.

The Internet has seemingly negated the role that Geography played in minimizing the impact that these individuals would have. Would a certain Florida-based pastor (turned Freedom/French fry chef and 2016 U.S. Presidential Candidate) been known outside the state 100 years ago, outside the country 50 years ago? Only to the devoted watcher. Also complicit in the rise of demagoguery is a willing mass media complex providing microphones and coverage for various rants (I’m sure you can find your own sources).

Anti-social media and its anti-social users can now draw on social media half a world away in order to push their own message.

(via BBC)

The above image was created by a (self-described) conservative Japanese woman (all from the BBC). The caption reads: “‘I want to live a safe and clean life, eat gourmet food, go out, wear pretty things, and live a luxurious life… all at the expense of someone else.’ ‘I have an idea. I’ll become a refugee.'” The artist posts to a social media page that also includes anti-Korean messages. As the BBC astutely points out immigration in Japan remains a controversial subject despite an ageing and declining population (regular Z Geography readers will no doubt recall failed public policy encourage Japanese Brazilians to immigrate to Japan).

The publication of this image immediately brought back memories (not even a month old, sadly) of the camerawoman for Hungary’s far-right Jobbik party, who was video tapped ignominiously tripping and kicking two or three people running.

For the last month, Z Geography has watched the inevitable troll war in anonymous (and non-anonymous) comment sections around the Internet. Demagoguery has no shortage of willing participants. The Internet has flattened the Geography of Hate.

But what is shocking to Z Geography is the level of impersonal detachment shown by the camerawoman and female artist. One woman from one culture immersed in an ongoing human dilemma found it perfectly acceptable to kick a little girl as she ran by. While another woman from another culture thousands of miles away found it perfectly acceptably to create an image based on a photo of another little girl to push a message of prejudice. Are we becoming desensitized to extremism? Probably.

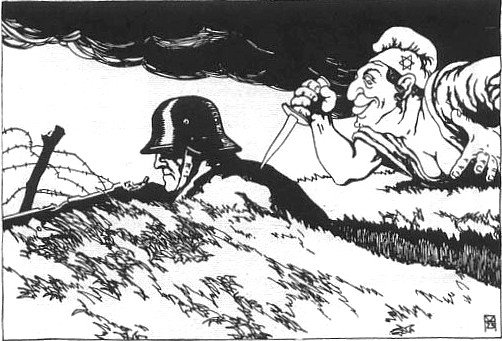

But Z Geography’s bigger concern is whether this activity – cartoons, videos of kicking, and comments defending it all – serves to legitimize extremism. It is unfortunate that there isn’t a historical precedent for this sort of thing.

Oh wait.

(via wikipedia): From a 1919 Austrian postcard showing a Jew stabbing a German soldier in the back. World War 1 ended in 1918, the Holocaust began in 1941. At least 12,000 Jewish soldiers died serving Imperial Germany.

Disclaimer: Z Geography does not advocate the curbing of freedom of expression and artistry on the Internet (and sees all three as public goods, in both senses of the word).