The German philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed that human knowledge could be organized in three ways. First, one could study the object specifically, toxicology, chemistry, geology, botany, and so on. Second, one could study an object based on time, history. Third, one could study an object based on its spatial relationships, Geography.

In the news this week was the revelation that the United States will be expending geopolitical power (i.e. deploying military personnel, via Voice of America) in checking the growth of violent Islamist movements in western Sub-Saharan Africa, to include Boko Haram.

(U.S. troops being deployed to northern Cameroon to assist fighting violent Islamists [Lake Chad in blue], via Voice of America)

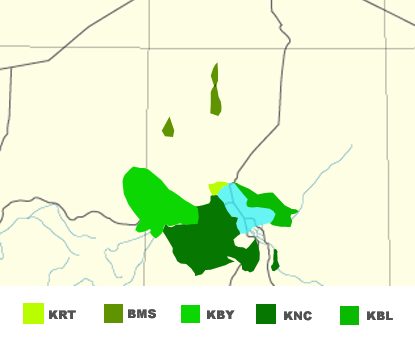

Kanuri linguistic groups, Lake Chad in blue, via Wikipedia using sources from Ethnologue

Geographically, two themes are relevant. First there is the ever-present legacy of colonialism. No, I’m not going to launch into the expected tirade about North-South relationships (at least not today). For this conflict, one relevant Geography of colonial history is the decline, fall, and subsuming of the Bornu Empire into the British colony in Nigeria, and the French colonies in Niger, Chad, and Cameroon. According to wikipedia, the Bornu empire was comprised of (primarily) of the Kanuri community. This is largely evident in a “visual analysis” of the maps above and below this paragraph.

Bornu Empire ca 1750, via Wikipedia

Having their own polity, the Kanuri people had (until the community’s nadir, just before absorption into the European colonies) control of their political, economic, and social destiny. How far this control (read: freedom) extended to lowest strata of society is an important question. With the empire’s break-up, the Kanuri were divided into several colonies, which eventually became independent states. These independent states, partial democracies (at best), were comprised of several (hundreds, in the case of Nigeria) other ethno-linguistic-sectarian groups – each seeking to maximize political, economic, and social influence.

The other relevant geographic point is, which follows on the earlier one, is the transnational nature of the Kanuri people. As Z Geography has written elsewhere, deconstructing the myth of the homogeneous nation-state (see popular writings on East Asia and Scandinavia for great examples) occupies a significant portion of geographer’s writing. Suffice to say that the transnational nature is, again, evident in the above maps and should be kept in mind while review the below – highlighting the distinct ethno-linguistic identities in Nigeria. Note that the map is from 1979 and is likely to have changed considerably.

Linguistic Groups in Nigeria (1979), via University of Texas

So the Kanuri used to have an empire and are spread across several states, what does that have to do with a violent Islamist insurgency in 2015?

Probably a lot, which brings me to history.

The other principal ethno-linguistic group involved in the Boko Haram violent Islamist insurgency are the Hausa-Fulani. Boko Haram is a loose translation from Hausa, “Fake Forbidden” and signifies that western education should be forbidden. In the place of the partially-free liberal democracy, the group (which was founded in 2002) advocates an Islamic caliphate (a theocracy) based on Islamic laws and jurisprudence.

The BBC article containing this information also mentions the Sokoto Caliphate, a primarily Hausa-Fulani project that also played a direct role in the decline of the Bornu Empire. If wikipedia is to be believe, Sokoto invaded Bornu because of the lapsed nature of their religiosity. The victory was shortlived (around a century) and the Sokoto Caliphate fell to the British by 1903 and elements within the former communities comprising the former caliphate (the Hausa-Fulani and Kanuri) has resisted British (and western) education since.

Boko Haram, however with a few notable exceptions, has primarily involved itself in the Kanuri areas of Nigeria (see map below). This implies, to Z Geography, that the Hausa-Fulani community is not quite on board with the combination of violence, Islamism, and (potentially) Kanuri-specific economic and political grievances.

Probable Boko Haram Attacks (Jan-2010 to Mar-2014), via Business Insider, data from ACLED)

Demographically, why should they be?

Based on the 1952/3 and 1963 censuses, the Hausa-Fulani population (combined) is probably the largest ethno-linguistic group in Nigeria (see reproduced table from a University of Oxford paper, 2005). To put it simply, under a democratic or republican system the largest ethnic groups can simply divide scarce state resources (say, rents from oil production) among themselves. After all, the 3 largest (in 1952) comprised 51% of the population.

| Select Ethnic Groups in Nigeria ca. 1952/1953 (from Mustapha, 2005) | ||

| Ethnic Group | Population | Percent |

| Hausa | 5,548,542 | 17.8% |

| Igbo | 5,483,660 | 17.6% |

| Yoruba | 5,046,799 | 16.2% |

| Fulani | 3,040,736 | 9.8% |

| Kanuri | 1,301,924 | 4.2% |

| Tiv | 790,450 | 2.5% |

| Ibibio | 766,764 | 0.3% |

| Edo | 468,501 | 1.5% |

| Nupe | 359,260 | 1.2% |

| Smaller Groups | 8,349,391 | 29.0% |

| Nigeria | 31,156,027 | 100% |

Indeed, this is the assessment of the Catholic Archdiocese of Abuja (the capital of Nigeria):

Today, political power in Nigeria has become a tribal zero-sum game. The popular assumption is that if the Hausas are in power, they are eating well while the Yorubas and Igbos are losing out. So, the Yorubas and Igbos simply endure and wait until it is their turn. Little wonder, political positions in Nigeria have become fiercely contested. Since Independence, Nigeria has been ruled by a handful of power-wielding oligarchs who, according to John Campbell, “have held power, lost power, and lived to play again.” Those who aspire to the highest office in the land cultivate the friendships of these oligarchs. Whether from the military, politics or business, these oligarchs seek to protect the parochial interests of their subordinates and clients to ensure their continued access to the spoils of office. (via Nigeria’s Guardian News)

But if the Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo – through sheer demographic weight – are able to sway elections and enjoy the benefits of the state’s patronage, where does that leave smaller, “major” minority groups like the Kanuri? To Z Geography, there are some potential political and economic grievances here.

But these grievances can be a call to action, not necessarily violent action. Leaving aside the nature/nurture debate, it is the contention of some academics that the Nigerian government’s violent crackdown on the group, especially in its early years, was disproportionately violent and served to justify the group’s narrative (see Serrano and Pieri: the Nigerian State’s efforts to counter Boko Haram, pages 194, 199): that the Nigerian government is illegitimate and should be replaced.

Into this complex conflict enters 300 U.S soldiers, marines, sailors, and airmen who will be conducting “intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance flights [as well as] enabling operations, border security, and response force capability.” In other words, the United States seeks to address the superficial effects of (at least one) corrupt and rapacious state, by supporting it.

In 20 years, when the Boko Haram group is (finally) stamped out, at the cost of millions of U.S. dollars, and (probably) hundreds of civilians’ lives. Another violent extremist group will take root in Borno state, espousing some ideology promising equitable access to resources and freedom from the yoke of an uncaring government dominated by an enemy ethnic group. This very same government will once again demonstrate that it is not beholden to this minority group, and violently repress it.

***

Organic state update: First, notice also that this violent insurgency in Nigeria has, and has before, cropped up quite far from the capital in Abuja. Second, there may also be an element of “effective capacity” here as well. The Serrano/Pieri chapter, noted above, also discusses the inability of local Nigerian police to effectively deal with local instability due to lack of training and equipment.